China's Era of 'Miracle Growth' Is Over, Say Scholars

China’s explosive growth, fueled by an expansion of credit that the country’s leaders lauded as good for its economy, has come to an end, several experts said this week – a sentiment that counters Beijing’s narrative that the world’s second largest economy is poised to overtake the United States.

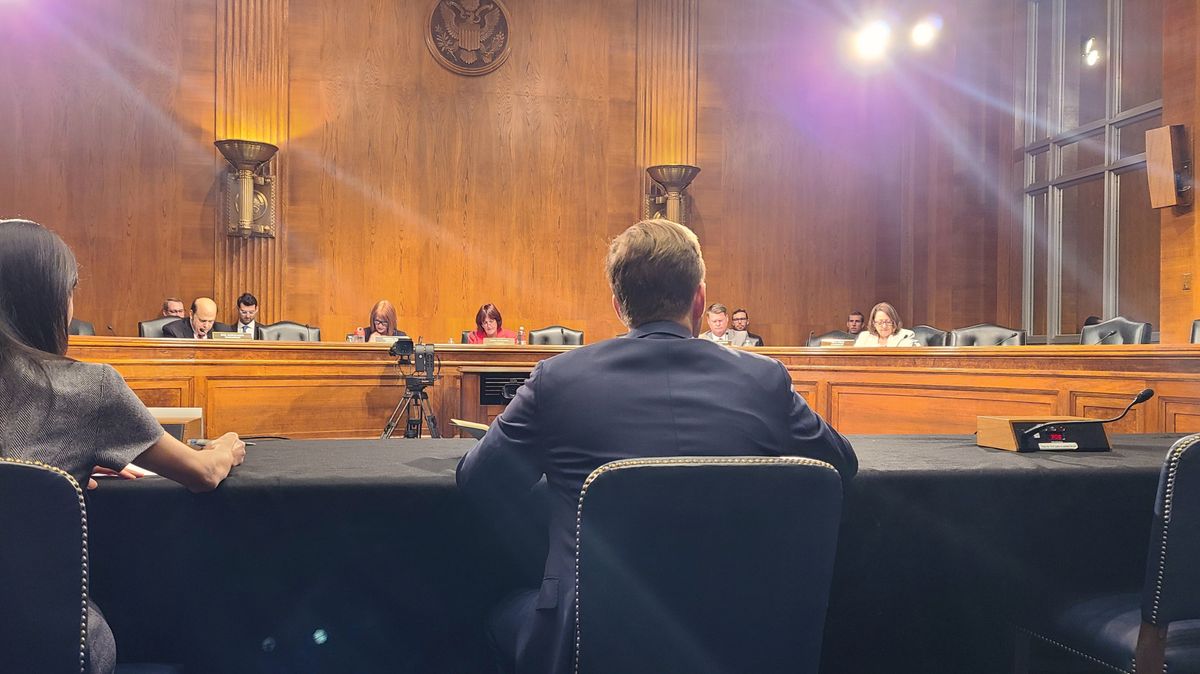

“Beijing will never be able to make a credible claim to global economic primacy,” Logan Wright, a partner at research firm the Rhodium Group said to a congressional commission Monday. He said in written testimony China’s weakness is “still widely underappreciated, and the United States no longer faces a growth challenge from China,” noting there are still other strategic challenges.

Wright said that spinning a positive narrative has been central to Beijing’s efforts to prop up the economy and “have focused on rebuilding confidence, among private sector firms, among consumers, and among foreign investors,” he told the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

As recently as 2022, Chinese authorities talked up a strategy to stimulate growth through the issuance of credit from the top down. Under the headline “Credit expansion bodes well for growth,” a July 13, 2022 story in state-run news outlet China Daily said, “In the latest effort to boost credit growth, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission published a circular…that urged more efforts from financial institutions to help maintain the rapid growth in mid- to long-term loans to the manufacturing sector.”

But Wright and the other testifying panelists said that China cannot grow its way out of debt. “Credit growth is limited, and inefficient in driving investment,” Wright explained, noting that much of the national debt falls to local governments, which are running out of capacity to service debt. In response to the 2008 financial crisis, Beijing tried to stimulate the economy by providing credit to state-owned enterprises and local governments. Those local authorities, in turn, used the money to build out infrastructure and invested in other public and private projects, relying on financing from state-owned investment vehicles, including sovereign funds. The strategy has run its course, experts agreed at the hearing.

Those immense sovereign funds obscure the Chinese government’s exposure to loss. Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, testified that for decades now, predating the leadership of Xi Jinpeng, China has found ways to leverage its foreign reserve holdings in ways that might be deemed too risky by western interests and by multilateral organizations that work to stabilize global currencies, like the International Monetary Fund. She calls them “sovereign leveraged funds” and said they are the result of “political engineering” and the “product of the state leveraging its financial and political resources to make it possible to capitalize a fund without relying upon a high-profit revenue stream like the export of commodities.” Liu said Beijing uses both investments that bear direct exposure to loss and those that bear indirect —that is, off the state’s balance sheet—to wield influence in markets. She said the practice started in 2003 with the effort to recapitalize China’s failing banks and reform its nonbanking financial institutions.

Xi has carried over the practice and amplified it, most demonstrably through the powerhouse sovereign vehicle known as the Silk Road Fund, which invested $10.5 billion in Europe alone during its first three years, she said, citing Bloomberg data. Overall, Xi promised the fund would invest $40 billion. Liu said the leveraging model inevitably leads to political conflict because it is the product of political strong-arming over who will control the investments and who will absorb the losses, rather than of financial innovation.

Liu said the United States should work with the European Union to protect companies in critical sectors from “undesired foreign takeovers" that may hurt the national interests of foreign direct investment recipient countries. “An important first step is to identify hidden sources of state-owned or state-sponsored investors by enforcing the rule of ‘follow the money’” in a coordinated FDI screening regime.

But exerting control measures on the global narrative has soured for Beijing, most notably in the recent disappearance of Chinese youth unemployment statistics. Co-chair of the commission Robin Cleveland noted in her opening statement that “by mid-2023 China’s official youth unemployment rate had soared above 21 percent, at which point the Party-state abruptly stopped releasing the data.”

“Although transparency into China’s economic data is vanishing, the country’s economic weakness is now far too pronounced for the CCP to hide,” Cleveland said. “International investors cannot have confidence in buying stocks on US exchanges or directly investing in China if data are inadequate, misleading, over-stated, censored or withheld.”